Cities are super-organisms; and like any living thing, they grow under the right circumstances, at the right time —or they don’t grow at all.

Many cities spring up at the nexus of trade routes, or spots that offer the locals some defensive or economic advantage. For example, Chicago’s rapid growth in the 19th century was due to its proximity to both the agricultural areas of the Midwest and the transportation routes to the East.

But while many urban centers are founded around industrial, agricultural, and trade concerns, Washington, D.C. (that acronym stands for ‘District of Columbia’) was solely designated from the outset as a political center; its particular location chosen not because of proximity to some resource or trade route, but because of its geographical “centrality” to the original thirteen states. (It was also on land that nobody wanted —a swamp, for all intensive purposes.)

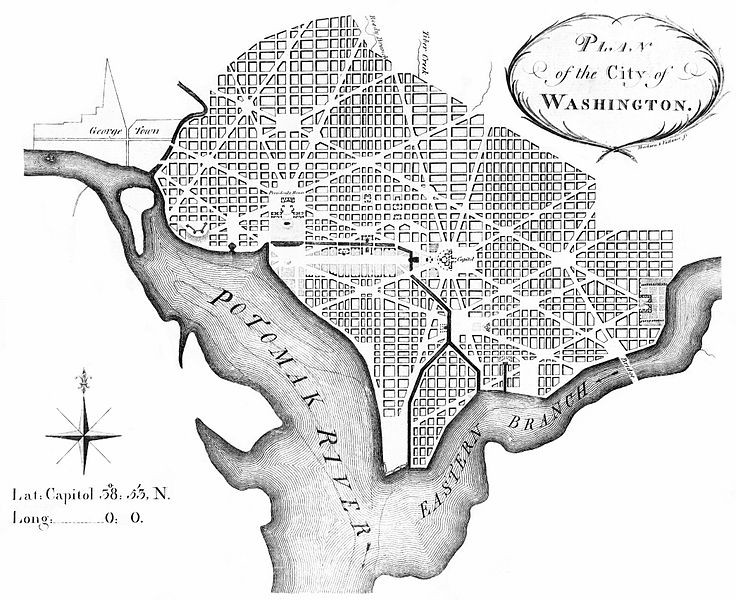

Major Pierre L’Enfant, commissioned to design the city in 1791, had envisioned an urban space that was, in his words, “en plus grand.” A 1791 map shows that he plotted the city out in a rigid spatial arrangement, with geographical features such as Tiber Creek (which no longer exists —at least on the surface) integrated effortlessly into an elegant whole. Take a look:

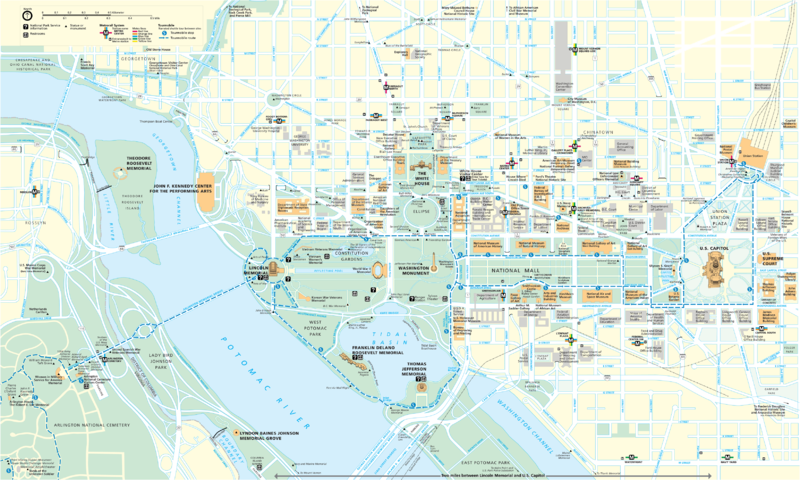

In the modern map, the settlement pattern has spread far beyond the bounds established by L’Enfant in the 1791 map, particularly into areas north and west. The “core” of the city (the National Mall and its immediate environs) have undergone further landscape modifications, including the addition of new monuments:

At first glance, it seems that this spread of neighborhoods beyond L’Enfant’s original grid and the massive alterations to the Mall are unconnected events. But these changes in Washington’s historical geography between 1897 and the modern day share an underlying cause.

Throughout the late 19th century, and into the 20th, the federal government grew larger and more powerful (government gonna government). New agencies were added, requiring new workers and infrastructure. To meet this demand, people began to migrate into the city in waves. For example, thousands of new federal workers entered the city during World War I and World War II, to help keep the war machine running. By 1940, the federal payroll in the city had swelled to over 160,000 employees.

The increasing numbers of federal workers needed housing, services, and necessities; a large service industry accordingly developed to meet these needs. In addition, after Reconstruction, large numbers of African-Americans fled to Washington in order to live within a federal protectorate. And on top of that, European immigrants filtered into Washington during the later 19th century, seeking the myriad opportunities there. Electric streetcars further propelled the growth of the far-flung neighborhoods beyond the original “core” designed by L’Enfant.

The federal government’s growth also led to the substantial alterations to the National Mall at the city’s heart. As Washington took on a more urban character in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many planners felt that the Mall should match the rest of the city in magnitude, rather than remaining in such an unkempt state. Starting with the 1881 reclamation of the tidal flats west of the Washington Monument, and continuing into the New Deal era with the Federal Triangle project, the National Mall underwent changes that included the addition of large federal buildings and substantial alterations to the landscape itself.

Northwest Washington

In 1888, the Washington street railway companies began replacing horse-drawn carts with electric trolleys. These new streetcars could travel further than the animal-dependent streetcars of decades past; an electric streetcar could efficiently climb hills all day, every day, without ever faltering or breaking into a pant.

The expansion of American commerce and settlement was often built on the backs of such technological innovations. Throughout the 19th century, the invention and refinement of canal and railroad technologies allowed farmers and entrepreneurs to drive outward from the “core” of the Northeastern United States into the resource-rich periphery to the south and west. Core and periphery, in turn, engaged in a symbiotic relationship: crops and unrefined materials would ship to the populous manufacturing centers of the east, while finished products (everything from manufacturing machines to pianos) would travel to the ever-expanding markets in the west.

Just as the invention of the steamboat and railroad helped create this national model, so the invention of the streetcar sparked a similar relationship between D.C.’s tidal-flat downtown area and what soon became known as “streetcar suburbs” in Northwest Washington and Anacostia. The “core” of the Washington area (downtown) provided the jobs and city services that allowed the periphery of streetcar suburbs to expand at an exponential rate. In return, the residents of the streetcar suburbs contributed manpower and funds to the sustenance and development of this “core” downtown, in a symbiotic relationship akin to the national model.

In the 1791 and 1903 maps, you can see that Washington is a relatively compact core on the tidal plain, essentially unchanged for over a century. In the latter map, there is scattered development to the north and on the eastern shore of the Anacostia River, but nothing nearly as substantial as what was to come.

At the turn of the 20th century, the area west of Rock Creek and north of Georgetown was sparely populated, at least compared to the center of the city. Notable buildings included the Tudor Place mansion, owned by Martha Washington’s step-granddaughter Martha Parke Custis, and the Naval Observatory, moved to its high point in 1893 to isolate it from the bustle and soot of downtown. The area around Mt. Pleasant, just to the east across Rock Creek, was similarly devoid of development.

There’s a reason for that relative lack of development: west of Rock Creek Park, the elevation is particularly steep. These are the hills that L’Enfant, during his initial survey of the geography, dismissed as only being impediments to settlement, suitable primarily for defensive garrisons (side note: all defensive plans failed during the War of 1812). Even today, many of the area’s roads are acquiescent to this hilly geography, curving and snaking, in marked contrast to the meticulous grid of the flat downtown area.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, it must have been a time-consuming effort to reach Northwest from downtown or the river. Even today, on paved streets and sidewalks, it is a long and sweaty hike up from Georgetown up to the “hillside” neighborhoods of Glover Park, Cleveland Park, or the Naval Observatory, particularly during the humid summers.

The electric streetcar, by substantially easing this burden of travel, promoted the development of areas far beyond the original “core” of Washington seen in these early maps. Just as, in the American West, towns sprung up along the railroad tracks, so ‘streetcar suburbs’ emerged along D.C.’s electric streetcar lines. The higher elevations west of Rock Creek enjoyed somewhat-cooler temperatures, particularly in the summer; that, plus the opportunity to avoid the stench, filth, and noise of downtown Washington, convinced many richer citizens to move into these new neighborhoods. For the middle class, streetcar suburbs also developed in Mt. Pleasant, Petworth, and Brightwood, areas still relatively idyllic compared to downtown.

As an example of this development, take Cleveland Park, the neighborhood north of the Naval Observatory and the Cathedral (named after President Cleveland, who used to summer there). Uriah Forrest, a Revolutionary War general, originally owned much of the area; succeeding property owners allowed the area to remain relatively undeveloped.

The area became more open to development in 1892, when electric streetcar rails expanded up Georgetown and Rockville Road (now Wisconsin Ave.) and Connecticut Ave. to the Cleveland Park area. An entrepreneur named John Sherman bought the old Forrest plantation and began converting it to residential housing; other commercial prospectors bought the adjoining lands. As soon as developers began to build, Washington’s richer residents rushed to occupy; apartments and houses went up; piped water flowed in. The neighborhood today is densely packed with residential and commercial structures.

The electric streetcar system died out in 1950, but the settlement of Northwest Washington continued. Now the automobile came to the forefront. Owning a car meant that people became less dependent on the limited number of streetcars; neighborhoods expanded again.

Tiber Creek, East Potomac Park, and the Growth of the National Mall

For much of its history, Washington existed in a very primitive state. It was, in the words of various 19th century observers, “a city of streets without houses,” the Capitol a “palace in the wilderness.”

This was not unexpected, especially by people who lived in the area at the time. The Potomac, while a sizable river, has little commercial value; unlike the Mississippi, it is not an effective trade route into the interior. The tidal basin was not an ideal site for cash crops like tobacco, even if space and soil quality had allowed for them. Washington may have been centrally located within the configuration of the original states, but the land itself had negligible value.

This lack of a commercial pulse meant that Washington stayed small for its first several decades, until an expanding government began to fuel growth. At that point, Washington’s rising status as a major city and as the heart of a powerful federal government necessitated that the National Mall, the locus of power, undergo some alterations into a more ‘appropriate’ form.

There was also the matter of the Tiber Creek, a small tributary of the Potomac that flowed through the center of the city. At least in the beginning, the city’s planners attempted to incorporate the creek into the design of the Mall. In a report to General Washington, L’Enfant wrote that a canal over Tiber creek would benefit the city by facilitating both trade and nearby residential growth. In addition, the canal would provide boats with an entrance “from the falls of the [Potomac] river into the Eastern branch harbor…which will be of the utmost convenience to all trading people, and the supplies of the city by markets.”

Further work on L’Enfant’s Tiber Canal, however, did not occur until 1803, when a young British architect named Benjamin Henry Latrobe, appointed Surveyor of Public Buildings, designed a modified version. As shown in the 1791 map, the canal would eventually run parallel to Constitution Ave. (past the marketplaces that lined the north side of the Mall), twist south just before the capital building, and eventually empty out into the Anacostia River.

Work on the canal did not begin until 1810, and it finally opened in 1815. It was a miserable failure. Shallow and stagnant, it quickly became a dumping ground for all manner of waste, including bodies from “Murder Bay,” a notorious slum in what is now Federal Triangle.

By the middle of the 19th century, goods could be shipped more efficiently by railroads overland than by boats up the Potomac. Consequently, the Tiber Canal fell into disuse. The human modification of the creek encapsulates a particularly heinous (and all too typical) aspect of 19th century development: a natural resource exploited to the point of ruin, only to be abandoned after it no longer proved useful.

In 1871, Congress approved the creation of a new government for the District of Columbia, consisting of a governor, a five-member Board of Public Works, and a twenty-two member legislative assembly. This territorial government lasted only three years before lack of funds and ill public opinion forced its dissolution. Nonetheless, the Board of Public Works conducted many public improvement projects during its short life, including the installation of large trunk sewers fed by miles of street mains. As part of these sanitary improvements, the Tiber Canal was converted to a trunk sewer and filled.

Few tears were likely shed at the canal’s passing; by then the waterway had long completed its transformation from a centerpiece of L’Enfant’s Mall to a gruesome nuisance. By the end of the 19th century, the canal had been filled in.

Throughout the 19th century, the rest of the Mall underwent other changes. In the 1791 map, the western half of the Mall, from the Washington Monument to where the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials now stand, is underwater; this area was subject to the tide, the water line nearly reaching the foot of the Washington Monument site, making construction impossible. (Legend has it that John Adams used to take his morning swim behind the White House.)

In 1881, Congress approved plans for dredging the Potomac, in order to improve navigation. The mud and earth from that operation was dumped into the marshy area west and south of the Washington Monument, reclaiming the land. Engineers also installed an automatic gate in the channel between East Potomac Park and the western part of the Mall; the resulting Tidal Basin controlled the Potomac’s ebb and flow. (The Jefferson Memorial, on the southern edge of the Tidal Basin, was built between 1938–1943.)

The streets and buildings around the Mall also underwent substantial modifications. In the 1897 map, there are none of the massive federal buildings around the Mall; instead, the area was lined with slums, including the infamous “Murder Bay.”

In due time, these slums were demolished, their residents pushed away from the “core” downtown into periphery neighborhoods, including Anacostia. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Federal Triangle (between Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues) and the area south of Independence Avenue were swept of their previous structures; various federal buildings, from the FBI Building to the National Archives, arose in their place.

Swamp

In his letters, L’Enfant never addressed whether Washington could effectively handle its eventual population. He had no reason to do so, given the context of his times: during the colonial and early Republic period, there was relatively little urbanization. Cities that loomed large in discourse were often little more than villages. And when Washington was actually established, under-population was initially a far more pressing concern than overpopulation.

But as the government grew, so did the city. The smelly tidal flats are gone (although the summer humidity remains a killer), and concrete covers what was once marshland and fetid creeks… but the ‘swamp’ moniker has never fully gone away, for reasons that now have more to do with politics than geography.